Three missing minutes, and more questions: Why did

Wayne Fella Morrison die in custody?

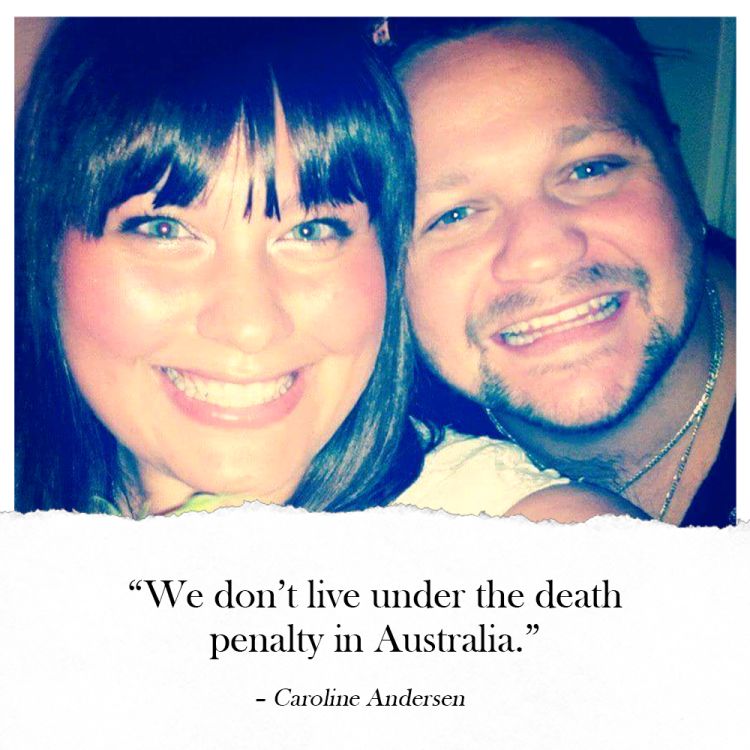

As the gruelling two-month inquest continues, the family of Aboriginal man Wayne Fella Morrison want someone to be held accountable for his death.

Caroline Andersen refuses to watch the CCTV footage showing the final, brutal moments of her son’s life.

Since the inquest began, she has been getting panic attacks and when the video is played for the courtroom, she leaves the room.

“I feel like I’m on trial,” Caroline tells NITV News. “I’m his mum, you know what I mean? I feel pressure. My parenting skills. How I raised him. It’s like I’m on trial for their lack of care.”

On 26 September 2016, Wayne Fella Morrison, a 29-year-old Wiradjuri, Kookatha and Wirangu man died at 3.50am in the Royal Adelaide Hospital.

In the week before his death, Mr Morrison had been taken into custody on remand. Due to overcrowding, he was held at the Holden Hill cells before being moved to Yatala Labour Prison where he was waiting to appear in the Elizabeth Magistrates Court by video link.

The coroner has so far heard how Mr Morrison told guards he expected to be released on home detention. Then hours before he was due to appear, there was an altercation between Mr Morrison and two guards in his holding cell.

Up to 12 guards wrestled Mr Morrison to the ground in a nearby corridor with CCTV played for the court showing him being pinned to the floor while his hands and legs were cuffed. A spit hood was placed over his head and a group of officers carried him in a prone position – chest down, face down – into a prison transport van.

Four guards accompanied him in the back of the van and for three-and-a-half minutes, no one knows for sure what went on. There is no CCTV footage showing what happened but so far the four prison guards involved have refused to give statements.

The guards themselves are yet to appear before the inquest, and it is unclear what they will say if they do.

“From the start I’ve said I just want to know the truth, I just want to know what happened, tell me what happened,” Caroline says.

The coroner heard testimony that by the time the van arrived at G-Division, the high security wing of the prison, Mr Morrison was non-responsive. CCTV video shows guards removing Mr Morrison from the van by dragging him out by the legs and laying him on the floor. It took two-and-half minutes before anyone began CPR. He died in hospital three days later.

This inquest, two years after Mr Morrison died, is already four weeks in, but with 48 prison guards involved it is expected to last two-and-a-half months.

So far, awareness among prison guards of ‘positional asphyxia’ has been a main focus. Positional asphyxia is a situation that occurs where a person is restrained in a way that leaves them unable to breathe. It is also a key issue in the currently suspended NSW inquest into the death of Dunghutti man David Dungay.

Much of the testimony given by correctional officers so far has focussed on the violence that occurred during on the day Mr Morrison was rushed to hospital. However Caroline and her daughter Latoya Rule say the descriptions they’ve heard of Mr Morrison do not match the person they knew.

“He was a painter [of Indigenous art],” Latoya says about her brother. “He had no real interactions with police at all. He probably saw them as protective people because of who he was.”

Growing up, Caroline says he was one of five children and a “free-spirit”.

“Wayne was always the child I didn’t have to worry about, in a good way,” Caroline says. “He always handled his own business. He was always able to deal and cope with, you know, the good and bad that life hands to you.”

As an adult, she says, her son was an outdoorsman and a fisherman. He was a stay-at-home dad with an eight-year-old daughter.

“He was the go-to guy,” Caroline says. “Men, real rough and ready men, have told me Wayne was the one they would go to when they had issues with their marriages or needed to talk about stuff.”

“He loved bees. He drew my attention to the importance of bees. And native bees. He taught me how they don’t have a sting.”

Since he died, their lives have been put on hold. Caroline used to work as a real estate agent, but no longer has it in her. Latoya, an Honours student at Flinders University, hasn’t been able to finish her thesis and has spent much of her time fighting to secure her brother some measure of justice.

Both say they are “very, very tired”.

The last few weeks have been a gruelling process. Cross-examination of the witnesses has so far exposed a lack of training and an apparent breakdown in processes in the lead up to Mr Morrison’s death.

Among other claims, the coroner has heard how one senior guard left the prison to get lunch after Mr Morrison was taken away in an ambulance, how staff were told not to fill out incident reports despite a direct order from the general manager and how the van which had been used to transport Mr Morrison was immediately put back into service before police had a chance to inspect it.

Of the three unit supervisors who have given evidence so far, all have initially insisted that there was nothing they could have done differently on the day.

When Officer Gordon Burnell, the supervisor in charge of the G Division exit, was asked under cross examination why he did not call for an ambulance sooner, he told the court that in a prison environment “different rules apply”.

“I decided that in the prison environment, the best thing to do would be to call a Code Black,” Mr Burnell said.

A ‘Code Black’ is a signal that is rebroadcast across the institution calling for all available staff to lend support.

Mr Burnell, who has been a prison officer for 28 years, told the court that officers may have been “cautious” in dealing with Mr Morrison due to the initial altercation that led to his restraint and that this led to the delay in performing CPR.

“We deal with these situations from time-to-time and we’re not sure whether they’re faking it,” he said.

In this way, the inquest into Mr Morrison’s death also has parallels to the 2014 death of Ms Dhu in South Hedland, Western Australia, where police and medical staff thought the 22-year-old Yamatji woman was faking her symptoms, right up until the point of her death from pneumonia and sepsis.

Separately, Detective Sergeant Lisa Pettinau, who was in charge of the initial police investigation of Mr Morrison’s case, described for the court how misinformation and delays in getting access left her feeling “frustrated”.

In one example, Ms Pettinau described waiting with police forensic teams on the day he was restrained to speak to witnesses and victims, only to be told that they had gone home.

“We were waiting and waiting. Then we were advised those officers had left for the day,” she said.

Ms Pettinau would later be told that this information was false, and that the corrections officers were still on site.

What it appears to show is a pattern where police were kept in the dark about what happened, with investigators not even aware of the seriousness of Mr Morrison’s condition. While police had been told an assault had occurred and he had left the prison in an ambulance, Ms Pettinau said she was not told the extent of his injuries until near the end of her shift.

“It was frustrating, yes. I expected a more collaborative approach,” Ms Pettinau said.

“We just wanted to know what happened here.”

That is also something the family would like to know.

“I find it absolutely disgusting and appalling that people that were there on the day, that were involved, can sit back and withhold, like it’s their god given right, information about what happened, in the van in particular,” says Caroline.

While both are waiting to see what results, they are sceptical about whether any real justice will flow from the inquest given the track record from similar cases elsewhere.

“No one has ever been convicted,” says Latoya. “After over 500 Aboriginal deaths in custody, nobody has been convicted.”

It is this, Caroline says, that has to change.

“I want changes made. But good changes. Real change. Not pretend change to make it look good… We don’t live under the death penalty in Australia,” Caroline says.

“I don’t want another death in custody, I don’t want to hear about another one. I want someone to be held accountable. I want witnesses to open their mouths, to stop staying quiet. I want the state government to follow the rest of the world and ban spit hoods.”